If you’ve ever seen John Carpenter’s ‘The Thing’ the name perhaps conjures images of Kurt Russell burning Cthuloid monstrosities in the snow.

The truth is a different kind of horror.

Project Iceworm was the name given to a secret US project to build hidden nuclear missile launch sites beneath the Greenland ice sheet.

A US Army illustration of a launch site for cut down two-stage versions of the Minuteman missile.

On one level, it’s a clever idea. From Greenland medium-range missiles would be able to strike targets deep inside the Soviet Union. The Russians would have little warning.

The US Military had a longstanding presence on Greenland – Thule Air Base, which served as an early warning station to detect Soviet bombers or missiles coming over the North Pole, but there was a problem – Greenland was Danish territory, and they never signed up to hosting missile silos.

Thule is still there, but it’s not a popular posting for USAF crews, and it costs a lot to run.

The Department of Defense’s solution to a potential diplomatic problem was to lie to their NATO ally. They announced a cover story about ‘building affordable military outposts in the ice-cap’. The first was to be Camp Century, built in a blaze of publicity and expensively filmed. You can see it in all it’s glory on youtube…

They couldn’t expect the Danes not to notice construction at all, but you can get away with a lot on a frozen wasteland. The real project Iceworm was to consist of 2500 miles of tunnels housing 600 missiles.

Camp Century had to start small. Even when it was finished, from outside it didn’t look like much – just a few ramps leading down to holes in the snow. Inside, the tunnels were more impressive, stretching for more than two miles under the ice.

As well as being a cover story, Century served as a live test for the techniques to be used in Iceworm. The base consisted of 21 tunnels - key features including a chapel, library and a nuclear reactor.

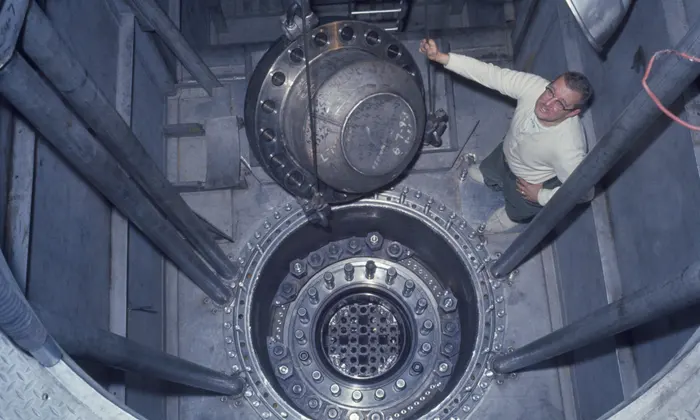

This is the nuclear reactor going in. All the parts had to be towed 150 miles over snow on tracked vehicles from Thule Air Force Base. It was the only practical choice to power the base, because diesel generators would need regular re-supply of fuel – hard to do somewhere this remote.

As well as all the impressive engineering, the creation of Camp Century provided some fringe benefits for science – some of the first ever systematic core samples from the Greenland ice-sheet. Unfortunately, these samples revealed a massive flaw in Project Iceworm.

The ice was moving. Inhabitants of the camp soon saw tunnels were constantly narrowing, and ceilings started to collapse under the strain. Two years after its construction, the ceiling of Camp Century’s reactor room had dropped five feet. Gradually, the camp was abandoned.

Project Iceworm was impossible. The nightmare of a vast array of nuclear missiles at the North Pole never came true. It had been doomed from the start by a failure to do some basic science. Ice always moves.

And that wasn’t even the craziest thing about it.

The whole project had been pointless from the word ‘go’. By 1960, nuclear missile armed subs already existed, and the first intercontinental ballistic missiles, the Atlas series, were coming into service.

Even if you thought nuking Russians was a great idea, there was no added value in Project Iceworm.

So why did the whole mess happen? Why spend millions of dollars and send hundreds of servicemen into the Arctic snow?

One possible answer is inter-service rivalry within the US military. In 1960 nuclear missiles were the future of warfare. Missile subs belonged to the Navy, and the ICBM’s and the bombers belonged to the Air Force. The Army was left out of the big game. Project Iceworm would get them in.

An early model Atlas takes off. A lot of them exploded on the launch pad.

But it didn’t work, and even the brief experiment of Camp century left behind radioactive waste, 200,000 litres of toxic chemicals and 24 million litres of untreated sewage buried in the ice. As global temperatures rise, it could soon start to leak out.

Probably a heating cylinder associated with the power plant.

Like so many of the messes from the Cold War, this one is still with us. Give me the homicidal alien shapeshifter any day.