It was a Boeing 727, an airliner about a hundred and fifty feet long, with seats for just under two hundred passengers. Thankfully, I didn’t have to fly it into the ground myself. There was a stunt team. I just had to work out how to make it happen, and how to film it…

It started in October 2009. I got a phone call from Dragonfly Film & TV, who were one of my regular clients as a freelance producer. They were making a documentary about aviation safety for Channel 4 & National Geographic. It was all going to be about a big stunt – crashing a real plane and analysing what happens to it.

The production had already been running a couple of months, the schedule required the crash to happen before the end of December, and they’d run into some ‘technical difficulties’ so they wanted me to join the team, figure stuff out, and make things happen. At this point, you might be thinking ‘Greg must be some sort of aviation expert’, but he really isn’t. He knows more about planes and how they work than 99.9 percent of people who work in TV, but that really isn’t the same thing. Really not.

I knew I didn’t have all the skills needed for the job, but I also knew there probably wasn’t anyone better, and if we could recruit enough real expertise, we could cover our gaps, so I got stuck in. Day one on the job was an eye-opener. There were good people on the team, but it was obvious we’d bitten off more than we could chew. The whole thing was astonishingly naïve. We didn’t have a plane. We didn’t have anywhere to crash a plane. Worst of all, we didn’t know why we wanted to crash a plane. We just knew we wanted to do it. The networks definitely wanted us to do it.

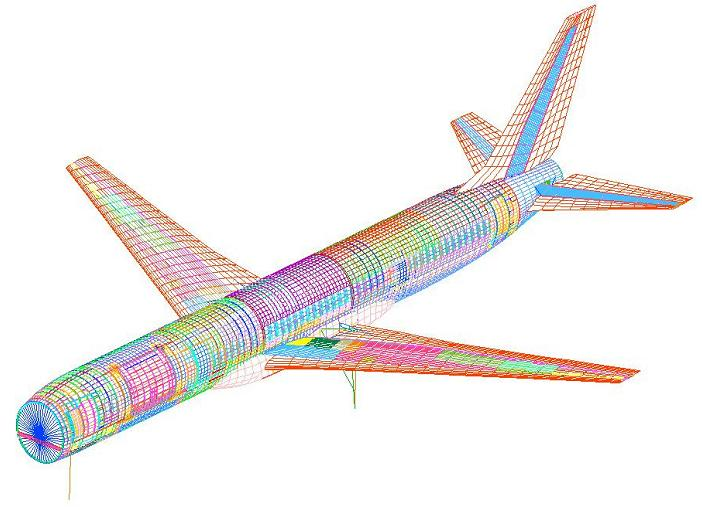

Research actually turned up some pretty good reasons to do the crash. We discovered all the current guidelines on aviation safety were based on computer simulations of what happens in a crash. The simulations are astonishingly precise, but nobody had crashed a real airliner since NASA in the ‘70s, so a comparison would be useful.

This is called a finite element model. The structural characteristics of the aircraft are modelled down to the last nut and bolt.

We quickly decided the Boeing 727 was the plane for us. Big enough to be meaningful. Old enough to be affordable within our budget (sort of). It had a unique feature that made it perfect – a staircase at the back that could be lowered in flight, enabling our pilots to jump out before the plane hit.

If you try jumping out of the front doors on any ordinary airliner in flight, you'll be sucked into a jet engine, or be decapitated by a wing, so this was a straightforward choice.

This feature had already given the 727 a place in history, as the only plane ever to be hijacked and then escaped in mid-air by the hijacker. DB Cooper (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/D._B._Cooper) famously disappeared in the skies above Seattle after jumping off the staircase.

The hijacking caused a fear of copycat attacks that never came

Artist’s impression of the disappeared criminal

We found our plane at a storage facility in Arizona. It was airworthy enough for a couple of final flights before its glorious death. We just had to convince the Federal Aviation Authority to let us fly it out of the country. They were understandably suspicious of TV producers wanting to fly ageing planes into the ground.

These places are weird in many ways. The aircraft here will likely never be used again, but they’re still worth a fortune.

The plane made a short hop to an airfield in San Bernardino, California, where it was to undergo modifications to make it ready for the crash. Thankfully, we did have some real experts on board for this stuff. The engineering and flying would be carried out by a company called Broken Wing, who were a bunch of ex-US Navy test pilots. Their engineer had regularly carried out work for the Navy, converting ordinary aircraft of all shapes and sizes into drones for experimental purposes.

The plan was this. One aircrew flies the plane until it’s about five minutes away from the crash site. They slow to about 100 knots and then lower the staircase at the back. One by one they jump out and parachute to safety, leaving the plane unmanned.

Obviously, an unmanned airliner could crash anywhere and do a lot of damage. That’s where the modifications come in. The engineer had tweaked the controls so they could be operated remotely. Another pilot, in a chase plane, would use the remote control to bring the airliner in on its final approach for the crash.

So, we had a plan, but we still needed somewhere we could crash an airliner without posing a risk to innocent people. A mistake could wipe out a couple of city blocks. We were looking at Mexico, mostly for economic reasons, because we’d need to hire a lot of people for logistical support and clear-up, and US wages would have broken the budget (which had never been adequate, but that’s not interesting). Our contacts in the LA film industry cautioned us against filming across the border – they said the help we’d hire there would be low-skilled and unreliable.

The truth was the opposite. Mexico was amazing. The Mexicans were amazing. After some searching, we found a great place. Laguna Salada is a dry lake bed in northern Mexico. Our location fixer, Omar Veytia, had just overseen local production of the Bond Movie, Quantum of Solace, and he did an amazing job getting the authorities on board.

It’s really hard to find a photograph that captures the scale of this place.

Back in San Bernadino, we started filming the modifications to the plane being carried out. Because the budget was so tight, I was acting as camera operator, and I noticed a potential problem. It was dark inside the aircraft – not dark enough to cause problems for the human eye, but these things matter to cameras. I could compensate by opening up the exposure, or bringing in extra lights, but I knew that wouldn’t be an option while the plane was in flight and about to crash.

The really difficult thing would be filming the passenger safety experiments we were setting up in the cabin. On impact the crash test dummies would shake around violently, and we’d need to capture that movement in slo-mo to understand what was happening. Slo-mo filming DEVOURS light. When you ramp up the frame rate, a sunny day in your garden can look like a darkened cave.

Troubleshooting the problem with a slo-mo specialist yielded an ingenious solution (his ideas, me just throwing problem after problem at him). LED lights (bright, with a low power draw) would run off an array of car batteries bolted to a steel frame in front of the passenger seats. This set-up would give them enough juice so an operator could turn them on before take-off and then the lights would last for the 2-3 hours the airliner would be in flight before the crash.

Experts advised us where to place the dummies around the plane to provide useful data. They’re expensive, so we didn’t have nearly enough.

But how were we going to get the footage from those slo-mo cameras? Tapes would almost certainly be destroyed in the crash. Solid-state drives offered greater survivability, but they would fill up quickly, and once they were recording, any delay might mean we didn’t get the shot. This was 2009, and digital wasn’t much of a thing yet (Panasonic loaned us two of the first Go-Pros ever released) – it existed, but it was a pain in the ass and you only used it if you had a good reason. Well, this was a reason. The slo-mo guy rigged the cameras and drives to record constantly, overwriting when they ran out of room. When the plane hit the ground, the force would trigger a switch rigged to an accelerometer, which would stop the drives recording a few moments later. The footage captured a few seconds either side of the crash would be what’s kept.

The big question we’d tried to answer in making the film was ‘What can you do to survive a plane crash?’ and the slo-mo filming of the dummies was going to give us the answers.

In some ways we’d been pretty smart figuring out all this stuff, but in one important way, we’d been pretty dumb. The reality is, buying airliners and getting permission from the FAA to perform dangerous experiments takes months. The production was running out of money and we’d hardly filmed anything. We were forced to cut cameras and crews from our filming plan for the crash. The killer was when we had to lose the helicopter that was going to follow the action and capture it from above.

At one point I went to the exec (my boss) and said ‘We’re doing something that happens once in a generation and there are provincial horseraces with better camera coverage’. There was just no point going through all this hassle if we weren’t going to shoot it in a way that the audience could see what was going on.

As the money ran out, me and the director, Srik Narayanan, had to leave the production and move onto other jobs. Production manager Luke Boyle stayed on to keep things moving before eventually giving way to his deputy, Amanda Hibbits. In the end, it took her three years, but she did it. She got the plane to Mexico, and arranged for a small town to be built in the desert to support filming and clear-up operations.

Our careers all moved on. A new producer and a new director took over. I didn’t know what happened until I saw the finished film. Amazingly, after three years, it all unfolded almost exactly as we’d planned. The Boeing hit the desert floor in a streak of dust and the nose broke off. No fire, but that impact would have killed people.

From a visual perspective we wanted a fireball, but this crash was the best possible result for experimental data.

There was one major problem. It missed the intended impact point by 2.5 kilometres. The only camera to catch the crucial moment was the one on the helicopter following the plane - the helicopter we’d had to cancel because the production couldn’t afford it. All the other cameras were in the wrong place.

Crashed planes are dangerous. Don’t go near one unless you know what you’re doing.

The reason for the miss was painful. On the day of the crash, the chase plane that was supposed to carry the remote-control team developed a mechanical fault. There was a back up plane, but it was slower. In the air it struggled to keep up with the jet-powered 727. The airliner slowed as much as it could without falling out of the sky, but it still left the chase behind. The remote pilot couldn’t let it fly on out of control, so he brought it down early.

That’s life in factual television. Even if we had the money, we can’t fake things like Hollywood. Reality gets in the way. You can’t guarantee anything. I’m just glad somebody (probably @moodle1234) found the money for the helicopter, and the film worked. Most importantly, nobody got hurt.

By now you’ll have worked out it wasn’t actually me who crashed the plane. I was one small part of a team of dozens who contributed, but I hope you enjoyed the story. It wasn’t terrific fun to live through at the time - thinking of the potential for things to go wrong took a heavy toll on all of us - but it’s a great memory.